Camp Chase: West Virginia Song Tells Civil War History

Old-time music from West Virginia is known for several family traditions that continue to this day, like the music of the Hammons family and the Kessinger brothers. Another well-known musical family was the Carpenter family who are said to be some of the original white inhabitants of what is now central West Virginia. The family produced many highly-regarded fiddlers like Solomon “Devil Sol”, Ernie, and French Carpenter. Like many of the songs associated with the Hammons family, Carpenter family tunes like “Shelvin Rock” tell the story of pioneer life in West Virginia. Another such tune that tells about West Virginia history is “Camp Chase”. Although the song probably came across the pond with another title from the British Isles (possibly related “George Booker”), the song took on a new name from a Carpenter family tale about the Civil War.

The story goes that Sol Carpenter was a prisoner at Camp Chase in Ohio who was released by winning his freedom in a fiddle contest. They say that around Christmas time the authorities decided to hold a contest and release the prisoner who could play the fiddle the best. All of the fiddlers had to play the same song, so to gain an advantage Sol threw in some extra notes that he made up which impressed the judges and they gave him his freedom. Sol taught the tune to family members like his son Tom, who taught his son French Carpenter, who in turn taught others like John Morris who continues to pass it on.

Compare John’s playing with that of French Carpenter. As traditions are passed down from generation to generation some things change, but other details remain the same. Let’s see what’s different or the same from another contemporary West Virginia fiddler, Mark Crabtree:

Whether or not the story is true, we do know for a fact that Sol Carpenter was a prisoner at the camp. Camp Chase was named after Salmon P. Chase, Ohio governor and Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary. It was established in 1861 six miles outside of Columbus, Ohio as a training camp for volunteers. Originally the prison held mostly Confederate sympathizers arrested for political dissent. In 1861 there were around 300 men, mostly from Kentucky and western Virginia (West Virginia was still part of Virginia until 1863). In February of 1862, after the battles of Fort Henry and Donelson, the camp received a large number of Confederate soldiers and officers as prisoners of war. By 1863 the number of prisoners reached over 8,000 men. This number decreased over time as officers were moved to Johnson Island in Lake Erie.

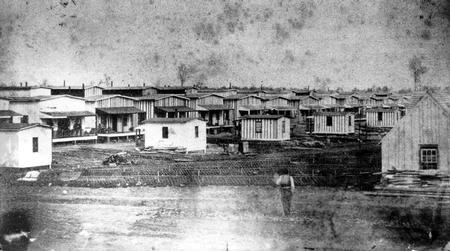

Camp Chase (photo from Ohio History Connection)

During the war over two thousand prisoners died at Camp Chase due to disease and starvation, about 8% of the 26,000 prisoners who passed through the camp. The facility was designed to house only 4,000 people and the cramped, close quarters led to the easy spread of diseases like typhus and pneumonia. In the winter of 1863-1864 an outbreak of smallpox killed hundreds. Food supplies were limited and went to the Union soldiers first, which could lead the prisoners with little food. In an effort to alleviate their suffering, U.S.A. and C.S.A authorities exchanged over 10,000 prisoners in November 1864.

Although living conditions were rough, music did provide relief for some prisoners. One prisoner at Camp Chase from Mississippi wrote:

“Although I am in prison, I have much fun. We play marbles and the boys fiddle and do anything to keep our spirits up, or do anything amusing, and so don’t be uneasy. I think I will get home in July, and then I will stay with you for some time. I have been in camp and in a fight that lasted nearly a week, and now I am in Camp Chase…” -P.L. Dotson, Company D, Twentieth Regiment, Mississippi Volunteers, Prisoner of War, to Mary W. Dotson, Brookeville, Miss.

In 1863 the camp established its own cemetery to bury the deceased prisoners, which contains an estimated 2,260 prisoners including bodies moved from the Columbus city cemetery and Camp Dennison. Camp Chase closed at the end of the war but the confederate cemetery remains today as a National Cemetery. A memorial arch was erected in 1902, and memorial services have been held every year since 1896.

-Ben Duvall-Irwin

Sources:

Clayton, Laura Keeble. “How Captain Samuel L. Cowan Escaped From Camp Chase During The Civil War”. http://www.storyhouse.org/kibby.html

Kline, Michael “Carpenter Family.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 12 July 2012. Web. 08 December 2018. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/976

Kline, Michael “French Carpenter.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 26 May 2016. Web. 08 December 2018. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/981

Knauss, William H. The story of Camp Chase; a history of the prison and its cemetery, together with other cemeteries where Confederate prisoners are buried, etc. Nashville, Tenn. and Dallas, Tex.,. 1906.

National Cemetery Association “Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery”. https://www.cem.va.gov/cems/lots/campchase.asp

National Park Service “Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery Columbus, Ohio” https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/national_cemeteries/ohio/camp_chase_confederate_cemetery.html

Ohio History Central “Camp Chase”. http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Camp_Chase